A World of Dreams and Dimensions

by Peter Frank

The cubists, it is generally accepted, revolutionized both modern art and modern perception by proposing a reality that exists in time as well as space because its discontinuities are no less apparent than its continuities. And this is cubism’s connection to surrealism; while the movement devoted to “the marvelous” would seem to have no pictorial relation to its (quasi-)rational predecessor, cubism’s liberation of empirical sight allowed surrealism to put sight at the service of the mind. In tandem, the two movements have allowed us to comprehend our dreams as complements to our realities – and to comprehend our realities as no less shivered and discontinuous than our dreams.

Seta Injeyan inherits spiritually from surrealism. Indeed, by her own account, an entire series of work has sprung from a single dream. The shifts that occur between subjects, images, perspectives, and contexts throughout Injeyan’s work happen because she draws out the visual realization of situations that have been intuited or discovered in her own psyche. But those shifts do not happen gradually. They happen suddenly, their subjects mutating radically upon passing over an invisible line or breaking up and piling in on themselves like reflections in a faceted diamond. There are plenty of seamless passages in Injeyan’s drawings, paintings, and enhanced photoworks, passages where things from one reality drift nonchalantly into whole other realities. But even in these passages Injeyan challenges logical progression, her changes in scale or tone or subject matter never subtle or optically subversive. They perturb our sense of reality, but they do not displace it. Rather, they fold back on themselves to yield a new coherence.

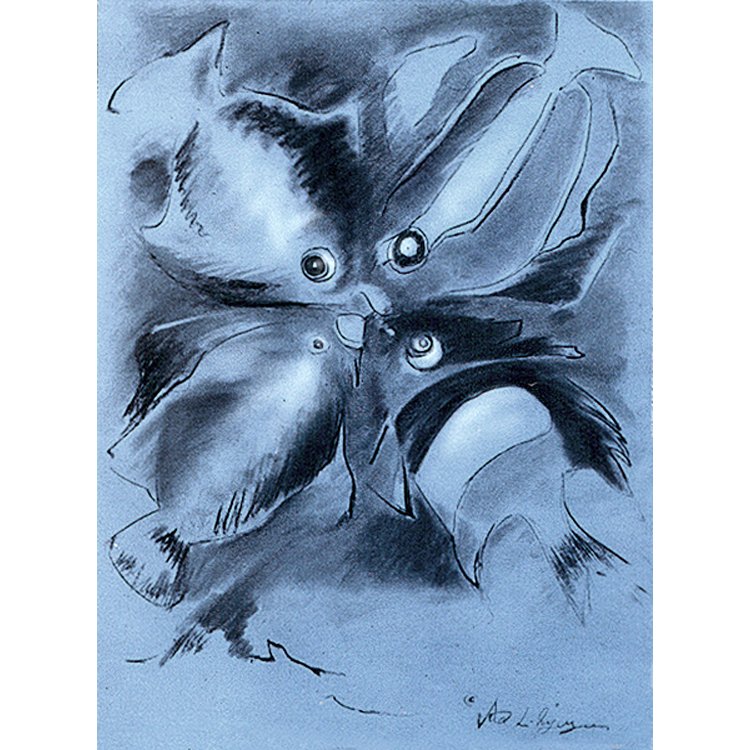

As with surrealist art, Injeyan’s certainly concerns image; but she reformulates imagery jolt by jolt, edge on edge, juxtaposition upon juxtaposition. The dream that sent her in this direction centered on a unified, heraldic, and deeply symbolic conformation, the arrangement of four fish into a square. But Injeyan did not simply experience such a symbol while sleeping; it evolved from innocent recollection of her childhood kitchen to a nightmare of pursuit by a menacingly metamorphosing object, an unlikely series of events as nonrational yet as vivid as any animated image. The persistence of fish in Injeyan’s early work clearly devolves from her dream, but her need in the face of that dream to make sense – even an alternate sense – of the everyday also accounts for the phantasmagoric resonance pervading her images, images that would otherwise be merely picturesque. Hers is a restless representation, a disorienting of fundamental sight in an attempt to make real the workings of the unconscious mind. palette, but here the dark tones are dramatically offset by very bright light, seen mostly through the far side of the predominating archways – as if Injeyan were slowly lifting the weight of dreams from her eyelids and passing into wakefulness. It is a wakefulness, however, laden with intuition yet to develop into certainty.

In her art, then, Injeyan is striving to dream lucidly. Over the course of her career she has evolved from weaver of dreams to contemplator of realities, but, just as she never left perceived reality entirely behind, she has not even now stopped her phantasizing about the things before her. In the late 1970s she employed the camera – that supposedly innocent machine, incapable of deception – to conjure a veritable field of dreams. Her works on transparencies (positive film) provided a medium in which one image could shine through another in a multidimensional layering of sight. Employing less straightforward photomechanical means to realize her “Fish” images and the even denser, stranger pictures that build on the works of Rembrandt, Injeyan made intricate her methods and results throughout the 1980s, moving from the gentle, almost childlike rhapsodies of skies populated with carp to dark, feverish apparitions populated with a mixed cast of human, if often mythical and always pre-modern, characters who have ventured out of a museum and into these ominous and often hilarious scenarios. The sunnier, more open montages that constitute the “Arches” series still rely on a dark

In the last two decades Injeyan’s sense of compositional assembly has endured, as has the sense of a reality heightened by multi-faceting. This pertains most notably in the various “Roads” series, where one interpretation of a view is embedded in another – specifically, a naturalistic rendering of a highway or road appears like a window inside a more expressionist rendition of that same vista. The embedded view is contiguous with the surrounding; that is, we see it where it is “supposed” to go, but we see what we all see inside that window, while outside it we see what Injeyan feels about that place, that road, that process of passage through a landscape (notably a landscape so evidently mediated by the human presence). As Injeyan employs it here, the combination of realism and expressionism is itself a surrealist parallel to the Gnostic belief that “What is above is below, what is inner is outer.”

Most recently, Injeyan has been painting what seem innocent, almost banal landscape and building scenes, sometimes populated with single figures. The bright light and insouciant subject matter set us up, however, for Magrittean touches that contradict normal optical logic. Windows and doors don’t simply demarcate passage from inside to outside, they warp that passage, as if the view of the outside were not part of the general surroundings, but part of the window or door. Especially in the context of what seem like gentle, restrained impressionist views, these unlikely reconstructions of human sight seem to explore alternate, still-folded dimensions of human awareness. But whereas before Seta Injeyan was alarmed about this rude intrusion into empirical reality, she now delights in it. She is no longer badgered by her phantasies; if reality itself can’t be tamed, then she has at least come to accept, if not revel in, its unlikelihoods.

Los Angeles

https://curatorsintl.org/collaborators/peter-frank